Confederate Medical Case Review: Avoiding Surgery for Battle Wounds (Confederate States Medical Journal Part 2)

Civil War Medicine carries a sort of morbid fascination with it. Most people hear those words together, and immediately, the imagination plays scenes of gruesome battlefield surgery, stacked piles of dismembered body parts, and overflowing field hospitals.

The study of Civil War Medicine has undergone a sort of renaissance in the last twenty years. Historians, myself included, have started to delve into this mysterious world to understand the difference between myth and truth. Civil War surgeons, as a whole, have received a bad rap from posterity. Many people think they were pointless, only exacerbating a problem, putting germ-infested fingers where they didn’t belong. Surgeons are probably the least-appreciated group from the Civil War. There aren’t any monuments or memorials thanking the doctors who burned the candle at both ends, subjecting themselves to countless dangers from battlefields to sick wards. These were surgeons who had to bear the heavy pain of losing patients and listening to the desperate pleas of soldiers asking for their pain to end or their lives to be spared.

Recent history has shown us that the Civil War was an incredibly important scientific moment. It pushed American medicine forward toward the rise to the top.

Learning from experience and contributing to medical science took a lot of trial and error. Doctors were forced to experiment with medications, surgical techniques, splints, prosthetics, and a whole body of medical equipment.

For Civil War Surgeons, the war was a tremendous learning experience.

While my podcast and course on Civil War Medicine aim to go much deeper on this point, for now I’ll just shorten it up. Due to pre-war medical standards and practice surgeons entered the military with very little in the way of surgical experience. In fact, early war stories talk of field hospital volunteer surgeons abandoning their posts so they could sneak back to the next level of hospital to get an opportunity to operate.

These surgeons entered the fray during a time when they would get more surgical and medical experience than they ever could have before the war. Think of the Civil War as an extreme version of a medical residency. Doctors now had advanced equipment. They could push past the 19th-century norms surrounding post-mortem exams and examine why patients died. They could understand pathology and surgical outcomes. These are a few of the big changes.

As I wrote in Part I, the Confederacy lost most of its saved medical data from the war.

They left behind two volumes of the Confederate States Medical & Surgical Journal. I’m going to dig through the journal in multiple parts here, so this is just a tiny sample of the medical cases presented in the journal. Let’s dig in.

Treating without Amputation, Leaving Things to Nature.

When most people think of Civil War Medicine, they think of amputations. Popular belief stems from our image of 19th-century medicine. Civil War veterans often recounted the piles of limbs.

Famous American Poet Walt Whitman served as a nurse during the Civil War. December 1862, he made his way toward the front, fearing that his brother George Whitman, an officer in the 51st New York Infantry, had been killed during the Battle of Fredericksburg. Whitman found his brother wounded but alive. During his time at the front, he was moved when he spotted a pile of amputated limbs, writing:

“I write this in the tent of Capt. Sims, of the 51st New York. Sight at the Lacy house- at the foot of tree, immediately in front, a heap of feet, arms, and human fragments, cut, bloody, black, and blue, swelled and sickening- in the garden near a row of graves.” - Walt Whitman, Diary Entry, December 22, 1862.

These are common images of Civil War medical treatment. Union soldier Andrew Roy, who served in the 10th Pennsylvania Infantry, was grievously wounded at the Battle of Gaines Mill on June 27, 1862. He wrote in his memoir Fallen Soldier: The Memoir of a Civil War Casualty:

“A rude operating table was constructed and placed in the shade of a tree, and the surgeons addressed themselves to the work of amputation.” - (Roy, 29)

This was the common belief surrounding Civil War surgery. Surgeons just lopped things off because there was nothing they could do.

Contrary to these visuals, amputation was used conservatively, especially as the war rolled on. Surgeons became more adept at determining the necessity of amputations. Physicians knew that surgery correlated with complications like gangrene, sepsis, and other infections they just didn’t understand why. Rather than eagerly hacking off limbs, surgeons tried to hold back when they could.

Confederate surgeons, like the Union, were often hesitant to perform surgery, especially as the war rolled on. As stated already, it was exceedingly rare for doctors to arrive at their postings with ample surgical experience. In the days before antibiotics, we can assume that a post-surgical infection was almost assured, but if surgeons had little experience in the field, they had to learn the hard way. Infection and surgery became correlated early on, making surgeons hesitant to conduct operations.

While infection was a concern, Civil War Surgeons also lived in a society that looked down on noticeable medical defects, deformities, or weaknesses. Civil War surgeries often left men maimed for life. Polite society didn’t allow much room for an amputee to indulge in daily life. Prosthetics came a long way during the war, but many men went through life without them. Wounds of the arms or legs were not the only disfiguring injuries. Facial destruction from bullets, shrapnel, or cannon shells would make it very hard to assimilate into the world after the war. Plastic surgery took a step forward as surgeons treated men recovering from disfiguring facial wounds.

The Confederate Medical Department studied the likelihood of healing without amputation.

The Confederate States Medical & Surgical Journal recorded several cases where gruesome wounds and injuries were left up to the body to heal itself. Surgeons kept track of the records, trying to use them to inform future operations.

On October 20, 1863, Confederate Dr. James B. Read received a wounded North Carolina soldier in his Richmond hospital. When 28-year-old James Jarrett arrived at General Hospital No. 4, he had been six days out after receiving a wound to his leg.

James M. Jarrett was a First Lieutenant in the “C” company of the 15th North Carolina Infantry. The 15th N.C. was attached to Confederate General A.P. Hill’s Corps in October 1863. On October 14, 1863, Robert E. Lee sensed an opportunity to attack the Union Army of the Potomac General Meade’s left flank. Instead of hitting a rearguard unit of Meade’s army, Hill’s Corps, including the 15th N.C., were sent into a frontal assault against Union General Gouverneur Warren’s entrenched II Corps at Bristoe Station, VA.

The official unit history of the 15th N.C. states,

“[they] charged the enemy in solid column over an open field of several hundred yards with Federal Maj. Gen. Gouverneur K. Warren’s Corps massed in front, and two (2) batteries of artillery occupying an elevated position on the right of the Confederate line . . . their lines were mowed down like grain before a reaper.” Lt. Henry Kearney, “Brief History of the 15th N.C. Regiment” (The 15th lost 24 Killed and 117 wounded in that short action.)

James Jarrett, a native of Cleveland County, N.C., took a minié ball to the left thigh at Bristoe Station on October 16.

The infamous conical minié ball was named after Claude-Etienne Minié, the inventor of the bullet. This, along with rifling, made bullets far more accurate and lethal.

The bullet that entered Jarrett’s leg shattered his left femur. The enemy round entered the front of his thigh, and oddly, the bullet exited the back of his leg, higher than the entry wound.

The hospital surgeons spent days treating the agonizing wound, trying hard to avoid surgery. Doctors gave the poor officer heavy doses of morphine, and he needed to be anesthetized with chloroform to simply have his bandages changed. Doctors packed his leg in a pile of pillows, and wet, cold-water dressings were applied to the wound. Cold-water dressings were used regularly as a tool to reduce inflammation, and most military surgery manuals recommended this method during the war. (See Frank Hastings Hamilton, A Treatise on Military Surgery and Hygiene, 1865)

The poor soldier’s agony forced the surgeons to try something else. On November 9, 1863, at 4 p.m., they put Jarrett under using Chloroform and opened up his leg. It took a seven-inch incision to examine the patient. The lower portion of the broken femur was jagged, and a loose part was sunk into the man’s muscle. A wood spatula was placed around the jagged edges to protect the soft tissue as the sharp points were sawed off, taking two inches off of his leg.

Muscle spasms kept the top, jagged portion of the femur on a sharp angle. The surgeons fought hard to free the bone from the tight muscles. A partial dislocation from the hip joint allowed them to move it back into place. With dirty fingers, the surgeons then picked out a number of sharp bone fragments, sometimes using their fingernails to pick them from the tissue. With the leg aligned, the doctors placed it in a firm brace, keeping the thigh in traction.

At 10 p.m., the patient was awake but required two grains of opium and a one-quarter drachm of brandy every two hours for pain. Miraculously, Jarrett claimed to feel better. By December 9th, Jarrett had improved drastically. He had an appetite again, and there was minimal discharge from the wound. He was able to move the leg on his own.

The removal of bone, allowing for a natural reattachment, was known as a resection. These operations were common during the Civil War but often left patients permanently disfigured. In instances like Jarrett’s, he would likely have one shorter leg. Sometimes, resections grew back at strange angles, leaving the patient with unusual-looking limbs.

Data was collected in the Confederate States Medical & Surgical Journal to understand the success of surgery.

Many surgeons kept meticulous case notes as they wavered between the support of operations or aversion to them.

Data was collected at one of the Confederacy’s most important and cutting-edge hospital complexes, built on Chimborazo Hill in Richmond, Virginia.

As it became evident the war was going to last much longer than both sides originally planned, the need for better hospitals arose. Both sides adopted a hygienic approach when building “general hospitals” outside of the dangerous heat of combat. They built hospitals according to Crimean War principles, using a “pavilion style” hospital. These hospitals were much cleaner, well-ventilated, and offered amenities like laundry services, clean kitchens, laboratories, and rows of smaller buildings where patients were spread out.

Pavilion-style hospitals became the norm during the Civil War. These large complexes were built, focused on hygiene and cleanliness. The idea was based on the Crimean War work of Florence Nightingale.

This photograph shows the inside of Harewood General Hospital, a Union hospital in Washington, D.C. This photo is representative of Civil War Pavilion-Style hospitals. Notice the numerous windows and ample space for each convalescing soldier.

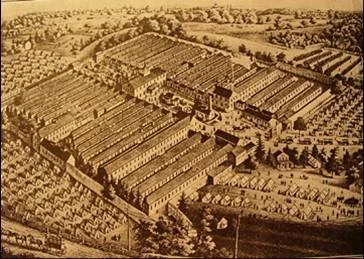

An aerial map of Chimborazo Hospital, Richmond, VA.

Chimborazo Hospital consisted of 90 wooden buildings that served as hospital wards with a total contingent of 150 buildings. Each ward held between 40 and 60 patients. The Confederate hospital treated over 75,000 patients during the war and was headed by Dr. James McCaw who divided the camp up into 5 divisions.

Dr. William A. Davis, an Alabama physician, was placed in command of Division 4 at Chimborazo Hospital. In 1862, Davis studied the success rate of femur wounds untreated by surgery.

Surgical treatment of femurs was always risky. In 1862, Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia saw a 38% mortality rate for femur amputations immediately after wounding occurred. Waiting 48 hours to amputate for the same injury shot the death rate all the way up to 73%!

There was hope that a more “conservative” operation called resection or excision would at least leave the patient with an intact but often useless limb. During a resection, the surgeon would remove broken, sharp, or deformed bone fragments, hoping the body could naturally bridge the gap. Confederate Inspector of Hospitals Francis Sorrel wrote that resections resulted in a higher death rate than amputations. Sorrel believed the longer operation time made a recovery lengthier.

Limb resections normally left limbs deformed and useless. Bones often grew back crooked and resulted in side effects like muscle atrophy and chronic pain.

Davis, leaving healing up to the body, had mixed results.

A patient named “J.C.” took a bullet to his left thigh above the knee on June 29, 1862, coming straight out of the back. Davis and his team put J.C. in a splint, and by August 31, 1862, he was furloughed and survived.

On June 27, 1862, a man initialed “S.H.” was wounded by three bullets that tore through his right femur, shattering the leg. The poor soldier also received bullet wounds to his left leg and shoulder. Despite the conservative treatment of splinting the wound, S.H. died on July 29, 1862.

Four more cases had mixed results, with two dying and two surviving long enough for a discharge from the hospital.

The head surgeon of Chimborazo Division no. 2, S.E. Habersham, recorded eight cases of femur wounds treated without surgery, with five dying and three surviving.

5th division Surgeon E.M. Seabrook had nine femur wounds treated without surgery, with two deaths, having a much higher survival rate than the other divisions.

The Confederate Medical Department quickly learned that it was best to perform surgery immediately if surgery was needed. The clinical data gathered at hospitals like Chimborazo mirrored work being conducted on the other side of the conflict, forever changing the future of medicine.

Civil War Surgeons were concerned with the risks involved in surgery.

Contrary to the idea that Civil War Surgeons indiscriminately cut off wounded arms, legs, and other appendages, they wanted to do what was best for patient survival. Seeing the incidence of infection following surgery made sympathetic physicians look for an alternative.

Data collected in the Confederate States Journal of Medicine & Surgery led to the conclusion that earlier operations, known as “primary amputations,” immediately following the receiving of a wound led to higher rates of survival.

This article is only covers a tiny portion of the massive body of Civil War medical information. I will be digging deeper into the Confederate medical journal over the next few weeks, looking at different aspects of Civil War Medicine.