Annihilation, 1914: The Belgian forces are pummeled to dust.

Liege, 1914. Germany introduces a secret weapon

The reason the fort had been built had already been meaningless. Its sole purpose was to protect the Belgian city of Liege, and decades of planning and creating the fortress ring around Liege had been futile. The German invaders had swarmed in and captured the city within days.

Under the ground, in the bowels of Fort de Loncin, the distinguished-looking Belgian General Gerard Leman paced anxiously. The German attack that began on August 4 eventually forced him to retreat from Liege and move into the old, musty fort. He had been in de Loncin since August 6, and now, on August 15, most of Liege's ring had already fallen.

Panicked messages flooded the fortress headquarters. Droves of German soldiers had already invaded Belgium and now occupied the fateful city of Liege, the city he had sworn to protect. At 0730 that morning, Leman received word that Fort Boncelles had surrendered. His orderlies shakily handed Leman another note. At 1230 hours, August 15, 1914, the German attackers had pounded Fort de Lantin into submission.

Leman’s heart sank. His garrison at de Loncin was one of only three remaining out of twelve forts surrounding the crucial city of Liege.

He shuddered as an earthquake shook the concrete over his head. A deafening explosion shook the walls, sending a shower of dust and concrete onto the heads of Leman and his staff. The General’s eyes felt heavy and numb with exhaustion. For days, the Germans fired their heavy mortars and artillery pieces toward de Loncin, his HQ. The fort was pummeled for endless hours.

Leman was commanding his first-ever battle. Forty-five years of service for the Belgian people, yet he had never commanded a unit in combat. Now, his last day of fighting was upon him.

Gerard Leman’s forces were tenacious at the start of the Liege battle. The German forces under the command of General Otto von Emmich made their push on Leman’s fortresses in the dark hours of August 6. Emmich tasked his forces with sneaking between the forts to take Liege from the rear. Instead, Leman’s fortress garrisons and the entrenched Belgian troops between them put up a tremendous fight, costing the Germans dearly. But that only lasted days.

On the night of August 6-7, the German 14th Brigade, under the command of German General Friedrich von Wussow, was ordered to move past Fleron under the cover of darkness. Tagging along was the future general, Erich Ludendorff. The Battle of Liege was fateful for Ludendorff, who was only there as an observer. The coming general’s task was to ensure battle plans stayed on schedule.

Erich Ludendorff was attached as an observer to the 14th Brigade. Ludendorff’s performance at Liege changed the trajectory of the war. He was later promoted to second-in-command of the entire German Army in 1916. That came after distinguishing himself on the Eastern Front. Ludendorff’s promotion to a major command came due to his performance at Liege. His memoirs of WWI show he looked fondly upon the campaign at Liege.

As they moved in the darkness toward Liege, a German Zeppelin conducted the first-ever air raid on an enemy city. The massive dirigible slipped over the city while shrouded in darkness. As the airship hovered over the city, the crew released a load of bombs. The Liege population was introduced to a new type of terror as nine civilians were killed by overhead bombing. As the zeppelin rounded over the city, fortress artillery clipped the airship, forcing an emergency landing.

The Zeppelin bombing of Liege was the first-ever aerial bombing attack. The bombs took the lives of nine civilians. The zeppelin took fire from the forts and was forced to land due to the emergency.

Ludendorff rode at the back of the long column of 14th Brigade soldiers. As the unit moved in the dark, he nearly plowed into the back of the group. They were stopped entirely. The baffled Ludendorff wheeled around the outside and rode to the front to discover the column was broken. The back half was lost. Ludendorff nearly led the unit toward annihilation as they rode into a Belgian ambush, but he quickly recovered and swiveled them back the other way.

Up ahead in the darkness, bodies were sprawled along the road. Von Wussow’s orderly stood confused, holding onto General von Wussow’s horse.

“Where is the general?” Ludendorff asked.

The orderly looked around blankly, dazed by the rain of artillery that had killed the men around him. With a flimsy hand, he pointed ahead. When Ludendorff rode on, he saw a pile of dead German soldiers surrounding a crater. Lying on the edge of the shell hole was the dead General von Wussow.

Ludendorff took the initiative. By the end of the night, he rode into Liege along with the rest of the 14th. The city's citadel sat quiet, and assuming the German forces had captured the fortress, Ludendorff pounded on the door. A group of Belgians opened the doors and surrendered at the shocking sight of the German officer. German forces now controlled Liege.

Despite Liege's occupation, the infantry assaults on the fortress ring were failing. Casualties were high, and the fortress defenses and entrenchments battered the German attackers. The German high command grew impatient. The time constraints made a move through Belgium crucial, as France needed to be swallowed up in days. Von Emmich was failing at his job, and the tactics started to change over the ensuing days.

The German forces grossly outgunned the Belgians. German 21cm-Morser 10s, 10.5 cm Feldhautbitze 98/09, 15 cm schwere Feldhaubitze 1902, and their larger mortars were the common accommodation of artillery during the Battle of Liege. The Germans put their guns to work mercilessly, pounding the concrete forts. For days on end, the Germans assaulted the forts with their artillery until they slowly started to surrender one after the other.

The German tactics switched from infantry-based assaults to endless artillery strikes. The Belgian forts were pounded with upwards of 250 shells per hour. The German forces holding Liege had an advantage now that they could fire their large guns at the rear of all Belgian fortresses. The German 21cm guns tormented the forts, drilling through the concrete walls as shells fell one on top of the other. Slowly, the shells inched closer and closer to the center of the current target.

The German 21cm Morser 10 was the main gun of the German forces at Liege. They pummeled the Liege forts at rates higher than 200 rounds per hour. The guns slowly chipped away at the forts, forcing their surrender.

Inside the forts, the brave garrisons held out under a torturing week of crushing fire. Every shell that slammed into the fort rattled deep inside the fortress, shaking concrete, dust, and any items not bolted down. The Belgian fortresses filled with blinding smoke that choked the soldiers inside as their ventilation system failed to keep up with the smoke from German shells and their own.

All the living facilities in all the forts were on the counterscarp, and getting to them meant exposure to enemy fire. The toilets, kitchens, and barracks were inaccessible for days. German artillery dismantled many of the plumbing and electrical systems throughout the fort, making the stench inside almost unbearable. Even the infantry garrisons who were set to hold the entrenchments were forced underground as the hellish artillery fire rained down on them.

On August 12, inside Fort Pontisse, the occupants heard an explosion so loud they thought the fortress magazine had exploded. The horrific sound was a German secret weapon.

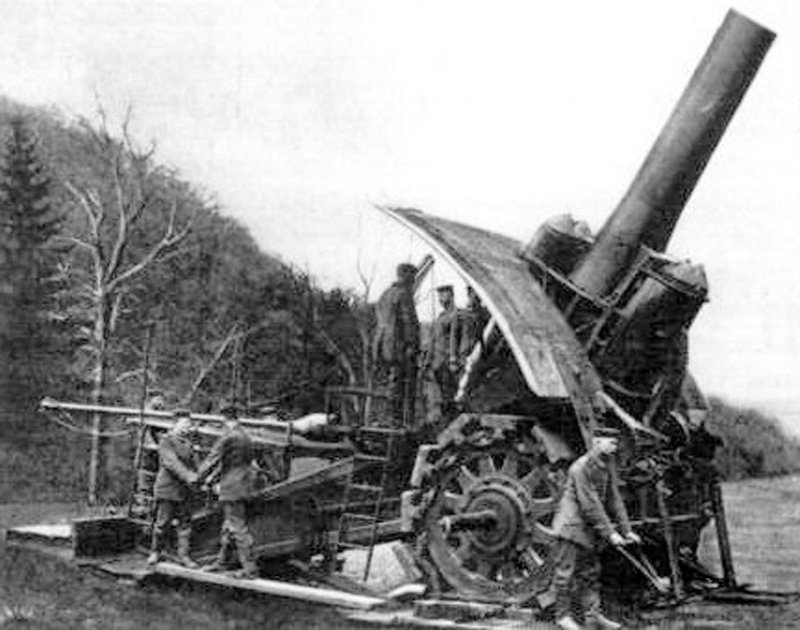

On the night of August 11, a German group of special tractors hauled in a massive cargo laid out on wagons. When the cargo arrived around Liege, the crews assembled a gun of unprecedented size. The German forces assembled the infamous 42cm Gamma-Gerat Howitzer, a gun so large it could fire a 2,000-pound shell over 9km. On the morning of August 12, the sound Pontisse occupiers heard was the German crew sighting in the massive gun.

At 1840 hours on the morning of August 12, the Pontisse force was in the sights of the 42cm German gun crew led by Captain Erdmann. With his binoculars pressed to his eyes, he ordered the crew to fire one of the massive guns. Binoculars were hardly necessary due to the sheer size of the explosion that missed the fort. He put the glasses down and called adjustments to the crew, but he saw white flags waving at the fort before firing. A group of German soldiers approached, assuming the garrison wanted to surrender. Instead, they merely wanted to leave while the massive guns fired, not to surrender. The Germans refused the offer as it grew dark. The gun crew went to bed, ready to pummel Pontisse in the morning.

The 42cm m-Gerat was a new weapon that could fire a 2,000-pound shell over 9km. The gun, built by Krupp, was first used in 1914 and was later nicknamed “Big Bertha.

August 13, the anxious garrison inside Pontisse gave up after four hours of the deafening fire. The ring of Liege slowly began to fall. Later that day, Forts Embourg and Chaudfontaine fell after German guns blasted them into surrender. By the evening of August 15, only de Loncin, Hollogne, and Flemalle remained.

The infantry support of the 3rd Belgian division held loosely to the ground surrounding the three forts. German artillery crushed the remaining citadels. Leman’s HQ had been subjected to days of torturing fire. Each shell ground closer and closer to hitting the fortress's center. The Belgian gun crews worked frantically from inside the fort to hit German patrols in the area, but the interlocking fire from other forts was now worthless, with most of them gone.

On August 15, 1914, at 1745, the German 42cm guns finished loading their 23rd shell. A defeated Leman slunk out of the central citadel of Fort de Loncin, leaving his office and HQ behind, and made his way toward the fortress's edge. The weak ventilation system made the fort untenable as Leman moved toward fresher air. His move to the outer reaches of the fort saved his life.

At that moment, a 42cm shell penetrated Fort de Loncin. The damaged concrete had been drilled, opening a way toward de Loncin’s powder magazine. The heavy shell slipped through the concrete wall and landed among 12 tons of black powder. The shell’s fuse activated the explosion that tore Fort de Loncin apart. The explosion lifted concrete, metal, bodies, wood, dirt, grass, and debris toward the sky. The fort's gun turrets lifted off their mounts like a cork, leaving a champagne bottle. Gerard Leman was thrown out of his citadel and knocked completely unconscious by the blast.

Germans and Belgians inspect Fort de Loncin after its destruction. The fort is now left as a pile of rubble, serving as a memorial and grave to those who died in the wreckage.

The next day, the last two forts finally capitulated. The Battle of Liege was a victory for Germany, and the vital rail and transportation hub was in the Kaiser’s hands. Leman, who miraculously survived the blast, was found unconscious by German forces who brought him to the German HQ. Leman’s first combat experience was his only combat experience. He spent the rest of WWI as a POW. Fort de Loncin became a tomb.

As the German forces moved beyond Liege, the battle showed the immense killing power of modern warfare machinery. The old forts of Liege were crumbled away by a new era of artillery that would come to represent World War I.

The performance of the Liege forts during the battle proved they were obsolete. Despite their obsolescence, the Belgian forces at Liege performed admirably considering the magnitude of their task. The Belgian infantry around the fortresses and the fortress guns held off German infantry assaults until the enemy forces were forced to shift their tactics.

The estimates of Belgian forces at Liege vary between sources, but at least 30,000 troops have defended the city. The 3rd Division, which defended the gaps between the fortresses, withdrew as the battle’s end became inevitable, withdrawing back toward Antwerp. Between the fortress garrisons and Belgian infantry, the defenders of Liege took over 20,000 casualties over 11 days.

The German forces, contributing over 30,000 soldiers and nearly 150 guns to the battle, took nearly 5,000 casualties at the hands of Belgium. The German troops were delayed for days, slowing their progression through Belgium and to France. The historical opinions surrounding the battle are mixed. Historians have argued whether Liege stalled the forces enough to stifle the Schlieffen Plan.

Regardless of the stalling action, the battle showcased a new era of warfare. Civilians were bombed by a German airship. Massive guns, never before seen in history, were towed to the front lines. Technology has made warfare far more destructive.

One prominent myth surrounding the Battle of Liege refers to the “Big Bertha” guns used. The destruction of the forts is often attributed to Germany’s new war technology. It was the 21cm howitzers that Germany pounded the forts with that ultimately broke them. The storm of fire that chipped away at the fortresses like a hammer ultimately pushed the fortress ring into submission.

The opening moment of World War I had passed. Imagine German forces marching through Liege as they go down to fight the rest of the war. They march alongside the smoldering remains of forts as Belgian prisoners are rounded up. Some move past Fort de Loncin and see the shattered concrete remains. The bodies underneath are left for eternity, and no doubt some who were still alive suffered their last moments under the wreckage. The Belgian guns are silent, pointed to where they took their previous shots. The archaic remains of an old war era were pushed aside.

German soldiers march on wearing various uniforms, most variants of the standard German field grey. New arrivals are weighted down with full packs and bedrolls. Most new arrivals carry full ammo bandoliers, and their rifles look brand new. The marching soldiers wear the pointed pickelhaube, and many are still covered with cloth, their unit numbers stenciled in red. As they move past the destruction, many are envious of those who could now call themselves veterans. The veterans who took Liege saw action, and these newcomers were eager to see their own before the war ended. There is plenty of action to come around, and many of these newcomers and veterans alike will never know the war’s end.

Beyond Liege, the withdrawn Belgian forces resisted fiercely as they retreated toward Antwerp. They were holding out long enough to give their British and French allies time to prepare and mobilize. Many of their comrades who fought at Liege are now German prisoners or dead, but their war is far from over. After defending Antwerp, most survivors went on to defend the Yser Riverfront near the horrific Ypres Salient.

What is about to become the most destructive war in history has only begun.