Calm Before the Storm: A difficult situation for both armies before the Battle of Liege, 1914.

German apprehension to invade neutral Belgium failed to change a thing.

World War I is almost synonymous with trench warfare. We have images of slop-filled trenches carved out of a decimated French or Belgian countryside. While this is accurate, the war was meant to be something different. It was meant to be a quick ordeal using man's newest machinery, designed to destroy and kill.

The European arms race of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries gave way to new military technology. Early in the war, this technology would have an immediate effect on pressing the German forces onto their objectives, but the novel killing machines were not going to speed up the conflict.

The technology of war would eventually force the Belgian capitulation at Liege on August 16, 1914. German guns penetrated the thick concrete walls of the fortress ring, but the Belgian delay was enough to squander Germany's hopes for a quick victory.

German forces, led overall by Helmuth von Moltke the Younger, needed to abide by the infamous Schlieffen Plan in hopes of ending the war quickly. The shared German-French border was off-limits to avoid a protracted battle. Movement through Belgium with a sweep down into France was the best route for von Moltke's forces, and the quickest move was to take place through Liege. The Belgian city on the Meuse River offered several advantages to the German war plan. If they took Liege, they would hold vital roads, railways, and waterways down into France. The region around Liege offered vital resources, especially for a German military that was landlocked on both sides. The area also gave occupiers access to coal and iron, which were available in the Ardennes region.

Beginning in August 1914, the Schlieffen Plan was finally called into effect. Germany had an opportunity to test its war powers. Germany first breached the borders of another guaranteed neutral nation, Luxembourg. On the night of Saturday, August 1, the German 69th Infantry Regiment captured the train station at Troisvierges. Over the next few days, several German soldiers from the 4th Army were wheeled in to build up strength on Belgium's borders. The battle for Europe was about to begin, thus kicking off the most violent era in human history.

The Belgian Situation at Liege:

The Belgians at Liege were led by General Gerard Leman, who had no combat command experience. He had an impressive peacetime resume, serving as a military school professor and rising through the Belgian ranks, but he had never commanded troops under fire. The closest thing Leman had to experience in war was gained as an observer in the 1870 Franco-Prussian War. In January 1914, the Belgian government gave him command of the Liege garrison, and when he arrived in the city, he was appalled by the conditions. Belgian soldiers stationed in the town were apathetic, not showing respect for their officers and keeping up a sloppy personal appearance.

Belgian Forces Defending Liege, 1914. This photo depicts the usual uniforms and equipment used by the Belgian Force in 1914.

The defenders of Liege were wholly unprepared for the upcoming war. None of the garrisons had practiced for a possible attack. The fortresses were unkempt, and the defenses surrounding them were non-existent. Gaps between the Liege forts were not covered by either infantry entrenchments or fortress artillery, making a sweep into Liege a possibility for any attackers. That would present a major problem, as any force occupying Liege could fire into the rear of any surrounding fort.

Belgian Forces in 1914: Belgian military members wore an unusual uniform. They wore dark blue overcoats above sky-blue pants and topped it off with a leather shako or top hat. As seen in this photo they used dogs as pack animals to pull machine guns and other heavier munitions on carts.

General Leman was horrified by the conditions of his garrison. Tensions were ever-growing, and as he walked the grounds circling the city, he realized changes were desperately needed. Leman trudged back to his command post in the city. His staff lived together in a modest house while the city's Civil Government occupied a grand palace. There, he conducted plans to defend the city.

Leman's plans were tedious but comprehensive. On June 26, 1914, one of his commanders, General Victor Deguise, presented him with an excellent defense plan. However, in a way that is typical of military and government endeavors, the plans were mired down by bureaucracy. Leman's superiors in government feared that preparations would make Belgium look bad. They believed that fortifying the area with guns and infantry would veer toward violating their neutrality. Leman pushed on, and his plan was finally approved in late July, just weeks before the war began.

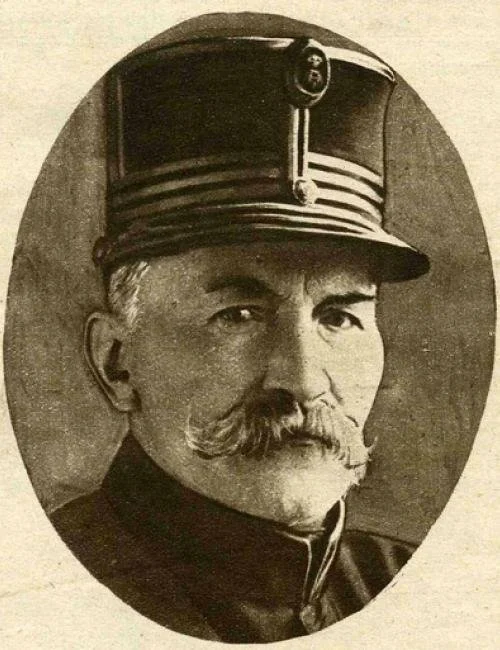

General Gerard Leman 1851-1920: Leman was a long-time but combat-inexperienced army officer. He recognized the desperate need for defensive bolstering around Liege but did not get approval until July 1914. Spoiler Alert: Leman was knocked unconscious when Fort de Loncin exploded on August 15, 1914, after a German 42cm shell penetrated the fort’s magazine. He survived the war as a prisoner.

Leman and his officers mobilized over 18,000 workers to dig entrenchments and move the Army's big guns to more ideal spots. Pontoon bridges were slowly constructed across the Meuse, where only two or a planned three were completed. Barbed wire, spikes, and new telephone equipment were used to prepare the area. The war was looming, and combat was looking to be inevitable by the end of July, so there was little time left to prepare. By the beginning of August 1914, the Belgian forces at Liege had been fully mobilized. Leman had the entire Belgian 3rd Division and those manning the forts.

Leman's forces were split up into three groups. An initial line of defense was created along the same line as the forts, where Belgian infantry occupied redoubts and trenches. A second line some 2km behind the first served as a fallback position for those in Liege. He set up a third line outside the city to the east to hold heights and other vital points in a desperate last stand.

The German Situation at Liege:

The German leadership created the German Army of the Meuse to capture Liege. General Otto von Emmich was selected to lead 60,000 men into the stronghold. Von Emmich planned to use his two Cavalry Divisions to interfere with communications between the fortresses and the city. Small German units were to occupy the fortresses, while larger infantry brigades were expected to move between forts and capture the city. The general's major plan was to infiltrate the gaps between fortresses, where he would deal with the forts themselves afterward.

Otto von Emmich was of Prussian origins. As a Prussian, he was no doubt committed to the German military. Von Emmich joined the Prussian Army on July 3, 1866, and spent the rest of his life in uniform. He served in the 55th Infantry Regiment for a decade. Unlike his eventual counterpart, Gerard Leman, von Emmich had seen heavy action in his career. During the Franco-Prussian War, he fought in two of the war's bloodiest battles, seeing action at the Battle of Borny-Colombey (August 14, 1870) and the Battle of Gravelotte (August 18, 1870). He had received the Iron Cross, 2nd Class, during the war. By 1914, he was General of Infantry and the commander of Germany's X Corps. He was hand-selected to lead the critical assault at Liege.

While von Emmich commanded the new Army of the Meuse, the overall leader of the expedition was Helmuth von Moltke the Younger. Moltke was the descendant of German military royalty. His uncle, the elder von Moltke, was the grand victor of the Franco-Prussian War and perceived unifier of Germany. The younger Moltke was beloved by his famous uncle, who catalyzed the younger's rise through the German ranks. After the elder died in 1891, Moltke the Younger became Kaiser Wilhelm's aide-de-camp. The famous von Schlieffen filled the German Chief of Staff position, and von Moltke the Younger was made his immediate deputy in 1904. In 1906, with the retirement of von Schlieffen, von Moltke succeeded him.

Helmuth Johannes von Moltke the Younger (1848-1916) He cut a German General’s figure. Moltke sought to avoid involving Belgium in any future conflict. He was obsessed with timing, fearing that delays past 1914 would make Germany’s chances in a major war impossible. Moltke led the German forces in the opening days of the war but was replaced after the French defeated his forces at the Battle of the Marne in September, 1914.

While von Moltke was a distinguished combat veteran, earning a citation for bravery during the Franco-Prussian War, he was inexperienced. Moltke's name carried him forward, but he would later be seen as a disgraced leader after he was replaced after the disastrous defeat at the Marne in September of 1914. Moltke was never crazy about the Schlieffen plan or the plan to invade Belgium. He proposed that Belgium would put up fierce resistance and that the bridges over the Meuse would be destroyed. Rather than using the full brunt of his armies to crash through Belgium, he split them up with one half set to take on a French assault through the Alsace-Lorraine region.

The Schlieffen Plan was set in stone regardless of Moltke's apprehensions surrounding the invasion of neutral Belgium. Moltke's staff was convinced the Belgian forces would crumble at the first sign of struggle. German intelligence monitored the situation in Belgium closely for years. Belgian forces had never undergone military exercises, and their fortresses lacked modern guns. This was all perfect for the impending war with France.

On the contrary, German intelligence informed Moltke of the situation in France. French fortresses would impede a quick movement through the region. The French resistance would be staunch, and Belgium was the only real way to maneuver. In that light, the invasion of Belgium was imminent.

Moltke's wavering on invading Belgium combined with his fears surrounding a lengthy war for Germany. Moltke the Younger secretly doubted the capability of his German forces to withstand a long war. The technologically advanced troops commanded by his uncle during the Franco-Prussian War crushed the French in six months. Moltke had reservations about any hopes of a repeat. Decades of conflict and impending European conflict had forced potential enemies to modernize. Heavily fortified regions in France and Belgium would send German forces into a questionable clash. The French in 1914 were no longer the inferior opponent they were in 1870 when they had suffered over six times the casualties of their German enemy. France was equipped with machine guns, railroads, long-range communication, heavy fortresses, aircraft, and modern long-range artillery.

For years before Moltke finalized plans to invade Belgium, he had been anticipating a war. His reasoning was driven by his fears of a lengthy war rather than his stance as a Warhawk. Every passing moment allowed potential enemies to grow stronger, and in the years before 1914, he had hoped the moment for war would come, but it never did. As the July Crisis of 1914 signaled the imminent war, he received intelligence reports from Belgium, observing Belgian forces preparing for an attack. Despite his dread of the invasion of Belgium, he watched as Belgium grew stronger. The pressure was mounting, and he had to make a move. Every day wasted gave his future enemies a chance to grow stronger, heightening the tension and anticipation of the impending war.

Conclusion:

Germany saw no other way to end a quick war besides an invasion of Belgium. There was a push to prepare for impending war for the Belgian forces amassing on the border city of Liege. These preparations came too late. Gerard Leman was slowed by the sluggish current of military and government bureaucracy, and all changes were not approved until the war was weeks away. In 1914, the July Crisis made war inevitable, and von Moltke the Younger's fears surrounding a protracted war made Belgium his only hope for a quick ending to the war. There was hope that despite Germany's violation of Belgian neutrality, the Belgians would step aside and let Germany on through, as they, too, wanted a quick end to the war.

On August 5, 1914, the Belgians resisted. World War I was kicked off, and Belgium's fateful defense bogged down the German forces, delaying their hope for a quick end to the war. In the next article, we will chronicle the futile but brave defense of the fortresses at Liege.

If you enjoyed this article and would like to support what I do please “Buy Me a Book” by clicking the link here. Any financial contributions are greatly appreciated and allow me to keep doing this.

Get my articles sent directly to your inbox by signing up for my FREE Substack Newsletter Here!